Damn! It feels great to be back. Thank you all for the amazing feedback on last week’s grid. If you’re enjoying Gridology, it would mean the world to me to forward today’s post to someone else who would like it. Have them join 318 curious and growth-minded individuals in receiving 2x2 breakdowns of questions regarding life, business, careers, and (mental) health.

Let’s dive in:

I’m going to let you in on a little secret. Nobody knows what’s best for you. You’re the only person who knows that. In today’s world, where self-help is as prevalent as a cup of coffee, we may lose sight of that concept.

However, it’s important to keep this in mind while reading today’s post. Every year, we are inundated with hundreds (thousands?) of books, blogs, podcasts, treks, and courses that try to convince you that your life would be better if you listened to their guidance. In reality, much of it is noise. Nobody really knows whether you should quit your job, get a dog, go to business school, finally go gluten-free, or ask your partner to marry you.

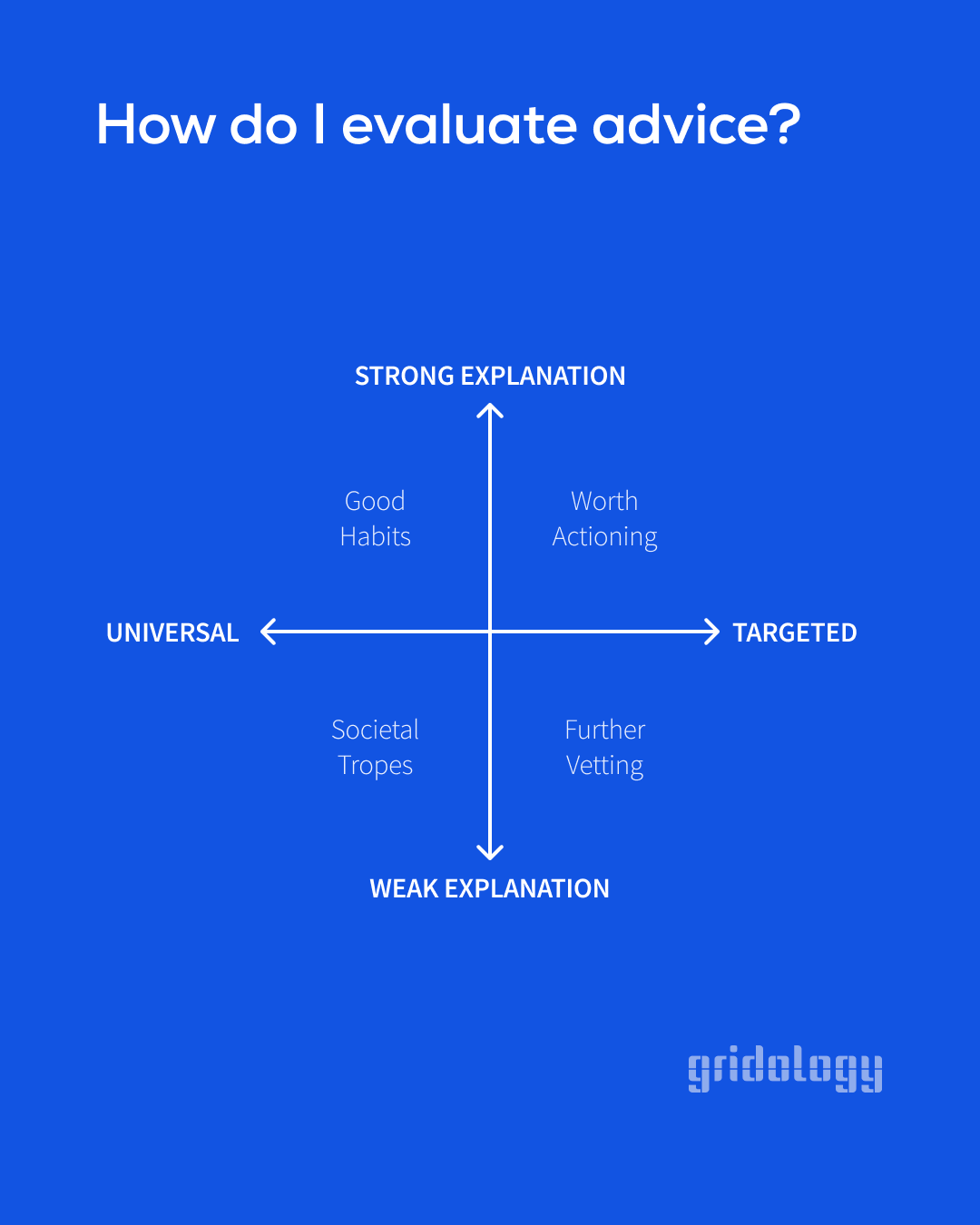

And, while Gridology probably falls in the broader category of self-help, I’ve always applied a take-it-or-leave-it approach to this newsletter. I let you all in on how I approach questions, and it’s up to you to apply them to your life, situation, or circumstance. And, as you’ll see in a moment, I try to write every newsletter so that it lands in the Good Habits quadrant.

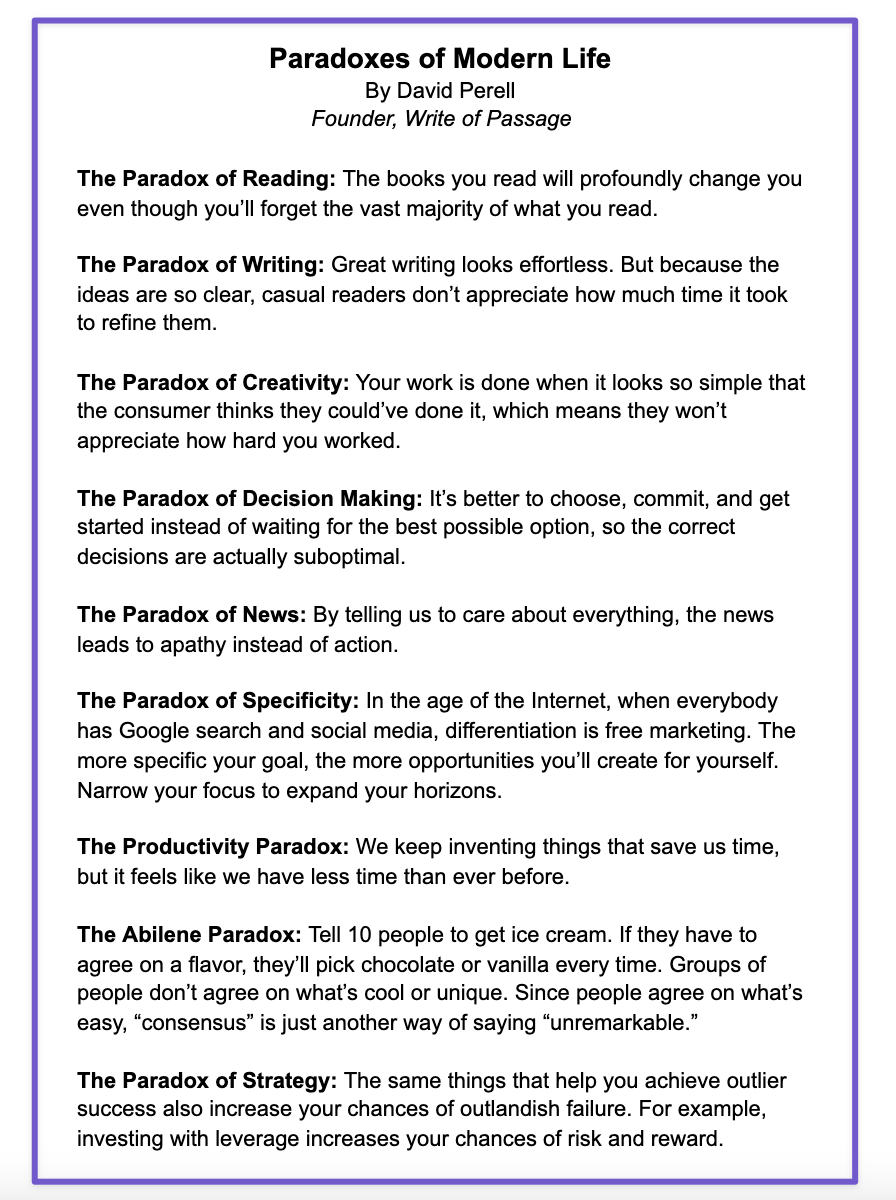

A few weeks ago, David Perell published a mini-essay regarding the paradoxes of modern life. His definitions are brilliant. I’ve embedded it below. Give it a quick read:

However, I think he missed an important one: The Paradox of Advice. I’ve noticed that when people share advice, it often is a tactic they use to convince themselves they’ve made a good choice. So, in reality, giving advice is a method for them to build self-assurance rather than to provide helpful guidance to others.

Here’s an example: Back in 2019, I was having one-on-one conversations with product managers to learn more about the role and seek clarity on how best to become one. I spoke to a wide range of industry professionals—some at startups and others at big tech. The advice I got was scattered. One said for me to find any role at a startup solving a meaningful problem, and then pivot into product management afterwards (spoiler: that was the path she took). One said for me to pursue a Master’s in Engineering and then I’ll find lots of success job hunting (spoiler: that was the path he took). Another said to find a small company and convince them to let me do product management (spoiler: you get the idea at this point).

Does this mean all of this advice was horrible? Not exactly. The final suggestion on that list ended up being the path that worked for me. When I joined Sounder back in May 2020, I had conversations with the CEO and COO where I discussed the value I could add to the team. A few weeks later, I was managing a big platform release and then planning an upgrade for our creator analytics dashboard.

What this does mean, though, is that when receiving advice that’s merely a regurgitation of someone else’s decision-making, don’t take it as gospel. More on this in a moment.

Without properly evaluating advice, you’re at risk of merely becoming someone else’s supporting detail. Humans are status-seeking animals—any opportunity we have to prove ourselves as smarter, wiser, or more accomplished is one we often take. What looks like assistance may prove to be something else entirely.

So, for today’s grid, I’ll be dissecting the framework I use to evaluate received advice.

On the x-axis, we have the level of specificity for the piece of advice. Published self-help content, for example, often is on the left half of the grid—the creator often fails to tailor the content to a targeted audience, purposefully taking a “one-size-fits-all” approach. One-on-one conversations with individuals you know well often fall on the right half of the grid. These people understand you, your personality, and your background and can offer valuable advice given who you are.

On the y-axis, we have how detailed the explanation is for the piece of advice. Above all, good advice has context. Because nobody truly knows everything about us, we need to understand the background history and reasoning for why people suggest what they do. These details unlock deeper evaluation. With strong explanations, we can assess whether the advice is coming from the right place.

Understanding the Grid

This grid is most valuable when evaluating whether a new piece of life, business, or health wisdom meets the high bar you (should) set for yourself before adjusting your strategy.

Worth Actioning

The advice is targeted and well explained. This is the best type of advice you could possibly receive. Often it comes from family, therapists, close friends, and professional mentors. The advice is given in a one-to-one format. What someone is advising you would not work for anyone else they know—it has that level of specificity. When I was debating leaving LinkedIn for a new job or to go to business school, a mentor I had for four years advised me to try using a different lens to make the decision. Rather than optimizing for the next year of my life—and what would be a better ROI—he told me to think about it in terms of regret and what I could gain outside of a professional context. When I’m 50-years-old, which road would frustrate me more if it was left untraveled? I realized that there will be plenty of jobs in my life but really one opportunity to get an MBA. Given my mentor knew my career goals and my personality, I followed his advice’s reasoning, and it resonated with me.

Further Vetting

The advice is targeted but poorly explained. This is the most dangerous quadrant of the grid because, without careful analysis, advice that should belong in this quadrant accidentally ends up in the Worth Actioning bucket. Too often we seek advice and just take it. We are so desperate for answers that when somebody exudes confidence and prestige, we believe they suddenly know best. Your friend who is kneck-deep in the crypto world and has been flipping NFTs shouldn’t become your financial advisor overnight. Networking conversations with industry professionals shouldn’t be considered prescriptive. In order to confidently take action from guidance, you need to understand the root cause of why someone is offering that advice. In the examples above, is your crypto friend trying to ensure his investments don’t go to zero? Is that connection trying to give himself a needed boost of self-confidence? These intentions are tough to identify. With deeper questioning, greater understanding can be gained. Above all, trust your gut—when something feels too good to be true, it probably is the case. As the quadrant is named, don’t just disregard this advice, continue vetting if the ideas are worth applying to your current strategy.

Good Habits

The advice is universal but well explained. I’m reading James Clear’s Atomic Habits right now, and it has transformed the way I block off my time and carry myself throughout the day. While Clear’s advice is universal, he explains the relevant background information you need to understand his perspective. The book begins with his personal story. When Clear was a sophomore in high school, a baseball bat hit him straight in the face. He needed to be put into a medically induced coma and attached to a ventilator to prevent unintended seizures. He writes:

“I returned home with a broken nose, half a dozen facial fractures, and a bulging left eye… it was eight months before I could drive a car again... I became painfully aware of how far I had to go when I returned to the baseball field one year later.”

However, despite this brutal injury. Clear transformed his life through well-designed habits to help him not only fully recover but also be selected as the top male athlete at Denison University and get named to the ESPN Academic All-American team. He puts real proof behind the systems he preaches later in his book. His explanations give me faith that if I listen to his advice, I can develop good habits.

Clear is just one example in a sea of strong content that can help improve your life. When digesting this information, digest it like a lawyer. Be skeptical. Demand explanations. Question everything. When you do, you will only implement the advice that helps you build good habits over time.

Societal Tropes

The advice is universal and poorly explained. Generalized content and poor individual conversations tend to land in this quadrant. Pithy quotes reign king here.

“Find a job you enjoy doing, and you will never have to work a day in your life.” —Mark Twain

“If you love something set it free if it returns its yours forever, if not it was nevermeant to be.” —Proverb

“Stay hungry, stay foolish.” —Steve Jobs

I’ll stop before I make you vomit. Taken alone, this type of advice is merely just a Societal Trope. They are so well-circulated that they’ve lost their meaning and intention. However, advice in this quadrant can still be useful, directionally speaking. Am I suggesting you listen to Mark Twain, quit the job you hate, and find your passion? Not exactly. However, these quotes won’t die because they represent some ideals worth striving to achieve. Would you rather be in a job you love than hate? Sure, but that’s easier said than done. For guidance that resonates and lands in this bucket, use them as a source of inspiration to go out and find better resources or people that can help.

Grid Shortcomings

This grid assumes all advice you are evaluating is directionally positive in nature. This framework breaks down if you’re engaging with objectively bad ideas that could get you hurt or in serious legal trouble.

This grid doesn’t mention trust. Having confidence in the places you are receiving advice is the foundation for this grid. You would never action or consider advice from someone who doesn’t care about you.

If this advice helps with evaluating advice (meta… I know), then great! Throw it in the Good Habits quadrant and send it to a friend if you think it would be helpful.

This is the framework I’ve been using for the last few months. I developed it because I found myself to be too trusting of others. When seeking advice, I'd assume everyone was trying to help me make sure I made the right choice. I realized lots of the advice I received from others was coming from a place to help them make sure they already made the right choice. It’s an important distinction that can be the difference maker.

I’d love to hear how you typically think about the guidance you receive. What did I miss? Feel free to comment or shoot me an email.

Life’s only as confusing as you let it be,

Ross