Well, the amount of news we faced this week could completely fill a normal newspaper for two full years. My thumbs hurt from refreshing my Twitter feed. Before we jump in today, I needed to share this tweet:

Now, for a topic that has captured a lot of my mindshare recently.

Here we go:

Three months ago I joined an online writing group called Compound Writing. It’s a collection of writers—ranging from hobbyists to journalists—who are looking to hone their crafts, be held accountable, and meet others in the online writing community. So far, I’ve made real online relationships with about a dozen people. These are people I’ve never met in person. Who knows if I ever will. (The internet, guys, amirite?!)

In the group, I’ve edited others’ work, publicly brainstormed Gridology content, and attended fireside chats with up-and-coming online writers. Without Compound Writing, these two Gridology posts would not have been what they were. The point is this: the organization captures and applies a concept that is essential to finance, health, personal development, building relationships, careers, and learning.

That lesson is compounding.

Compound Writing anchors itself in the idea that a little progress made every day towards being a better writer can exponentially change your ability to create better content and grow your audience.

The creator community on Twitter loves to talk about compounding. Taking a page out of Albert Einstein’s playbook, Jack Butcher visualized the concept of compounding being the eighth wonder of the world (click to read the full thread):

Given its magic, you’d expect everyone in the world to compound something—whether it be their finances, a skill they’re trying to master, or a career goal. The tricky part about compounding is that it’s extraordinarily difficult. It requires patience, dedication, and mastery… and a long (and sometimes unknown) time horizon.

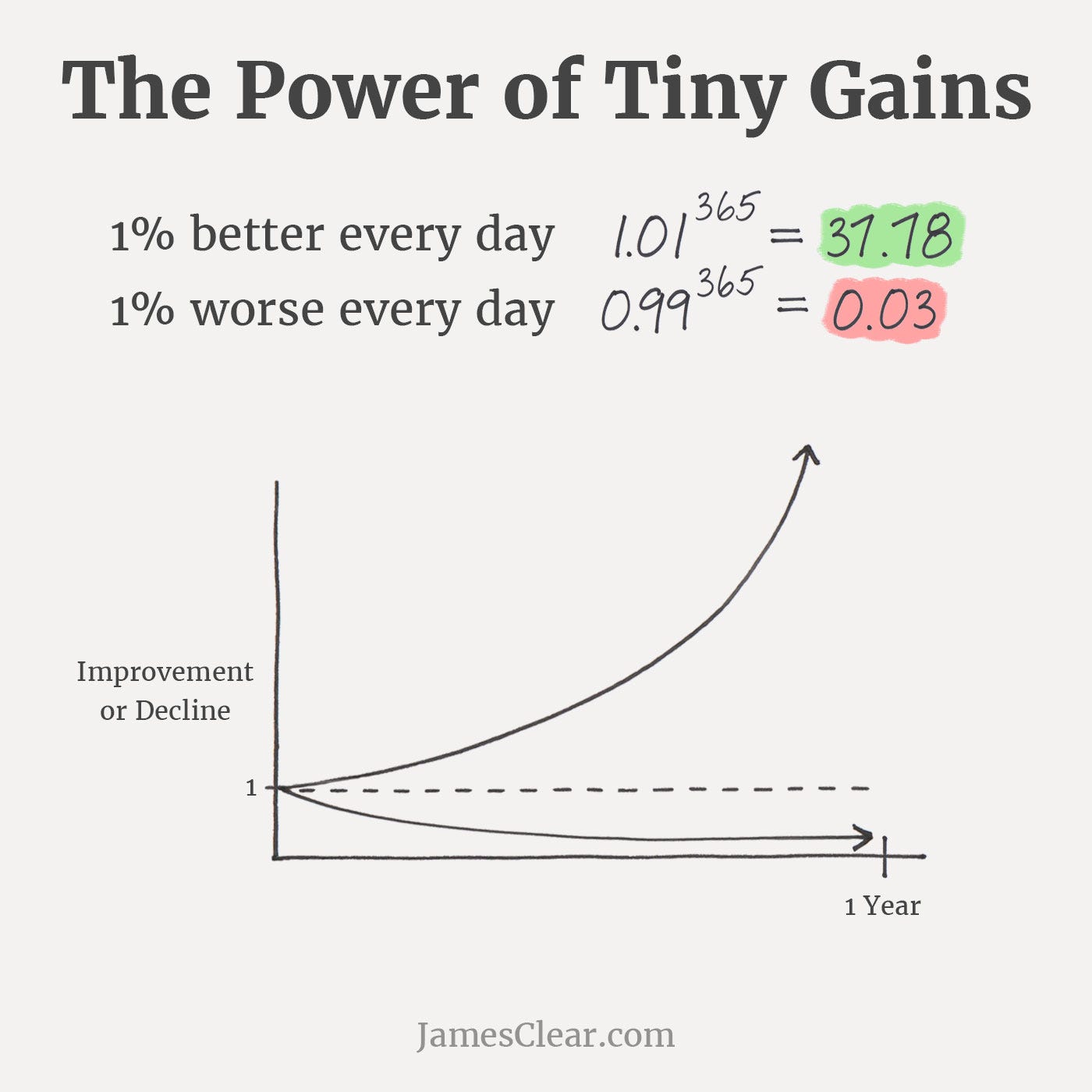

Regardless of how challenging compounding is, the gains are very, very real. James Clear, author Atomic Habits, says:

…[I]mproving by 1 percent isn’t particularly notable—sometimes it isn’t even noticeable—but it can be far more meaningful, especially in the long run. The difference a tiny improvement can make over time is astounding. Here’s how the math works out: if you can get 1 percent better each day for one year, you’ll end up thirty-seven times better by the time you’re done. Conversely, if you get 1 percent worse each day for one year, you’ll decline nearly down to zero. What starts as a small win or a minor setback accumulates into something much more.

Here’s how James Clear visualized this concept:

Source: JamesClear.com/marginal-gains

The math checks out. Compounding every day is a superpower.

If you need more proof: Let’s say you’re half as consistent—meaning you improve 1% every other day for a year—by the end of the year you’d only be six times better (not 37 times better) than where you began. Going further, if you focus your improvement just on the weekends for an entire year, you’d only become 2.8 times better.

Warren Buffett, the godfather of compound interest, thinks about exponential growth in very real terms. For every transaction, he considers how much it could cost him in future wealth:

“His friends and family regularly heard the young Mr. Buffett mutter things like “Do I really want to spend $300,000 for this haircut?” or “I’m not sure I want to blow $500,000 that way” when pondering whether to spend a few bucks. To him, a few dollars spent that day were hundreds of thousands of dollars forgone in the future because they couldn’t compound.”

So for today’s grid, I’ll be breaking down what it takes to compound—your time or your money—successfully.

On the x-axis, we have the size of the task you’re trying to complete. Compounding is easiest when the task is as simple as possible. I wrote about this concept back in August when talking about how to build habits. The most successful way to start compounding is with small tasks. It’s much easier to commit to writing for 5 minutes every day rather than to write for two hours every day.

On the y-axis, we have your level of consistency. As mentioned, how consistent you are dictates how much better you get over time. Carving out time every single day to do whatever it is you want to do will have incredible, eye-popping returns years later.

Understanding the Grid

This grid’s intention is to help you migrate important initiatives to the top right quadrant—that’s where you’ll find exponential growth. However, not everything you do in life needs to accomplished by compounding over time.

Exponential

You focus on small wins consistently. The beauty of compounding is consistency is king, not the level of effort. Just look at 1% daily improvements can do when considered over just on year. It’s wild to think you could be lightyears ahead of where you are today when you added simple and consistent activities to your life. I saw exponential growth when I focused and developed an accidental system of compounding to learn Python. Every day at the office, I carved out a little bit of time to learn Python for a team project. Often, this focus would carry over into the weekend—I’d read through tutorials and watch videos so I could start the week off ready to work. At the end of each month, I’d reflect back to where I was at the start of the month in complete shock. Knowledge was building in a way that allowed me to learn more, faster. Learning certain concepts allowed me to master new ones faster than the old ones. Time spent learning in the past unlocked increased learning potential for the future.

Scattered

You focus on small wins inconsistently. Hobbies, unprioritized ideas, and experimentation fits in this quadrant. Not everything in life needs to be looked at through the lens of compounding. I have a scattered approach when it comes to crossword puzzles. Once or twice a month I get laser focused on doing crosswords. I find them to be a relaxing and fun way to unwind before bed (when I’m not frantically refreshing Twitter, of course). However, I don’t complete puzzles consistently enough to get better, meaning I’m permanently in a loop where I can only answer the Monday puzzle in the New York Times without asking for hints. With a more consistent focus, perhaps I could make more progress improving from Monday all the way to Sunday (where the crossword experts spend their time). While crosswords are just an occasional and fun activity for me right now, if I ever got serious about expanding outside of Mondays I’d figure out a way to embed 20 minutes for a puzzle every single day. With that consistent time commitment, I’m sure I’d see quick progress to more challenging levels after a year or two of dedicated effort.

Bursts

You focus on big wins consistently. These goals take time to accomplish, but once completed, you check them off your list and move onto the next thing. It’s buying a few stocks, doubling your money, and immediately selling to hold cash. It’s training for a marathon and then giving up running. It’s buying a guitar, learning how to play a Wonderwall by Oasis, and then calling it quits. With bursts, there’s a set goal at hand. This is where I had focused much of my time until recently. I was dead set on finding large, meaty objectives to sink my teeth. In doing so, I would achieve the given objective but fail to dream bigger—forgetting to think how this objective could be just a stepping stone for something bigger down the road. Now, I’m more determined to pick skills that I’m interested in pursuing for years at a time. That way, I can start to see compounding at work. Whether it is Gridology or not, I’m making an investment that my writing can improve by compounding my online writing practice.

Aspirational

You focus on big wins inconsistently. When you set big goals without a real plan for achieving them, you’re doing the opposite of compounding. You’re hoping you strike gold. Want to write a world-class fiction novel? That doesn’t mean writing for eight hours a day a few times a year. It should mean writing a little bit every day for years. It should mean writing a bunch of books before ultimately writing the book. When you land in this quadrant, it’s because success looks so distant that spending time feels like it could be a waste. Why do so many children say they want to be an astronaut, an actor, or a professional athlete when they grow up but few rarely realize that dream? It’s because the road to success is winding, difficult, and long. It’s not easy to become the next Buzz Aldrin, Brad Pitt, or LeBron James. It requires years of practice, studying, and experience. The lessons compound. The skills improve faster and faster. Take Pablo Picasso, for example (story originally comes from What They Don’t Teach You at Harvard Business School by Mark H. McCormack):

It always reminds me of the story about the woman who approached Picasso in a restaurant, asked him to scribble something on a napkin, and said she would be happy to pay whatever he felt it was worth. Picasso complied and then said, “That will be $10,000.”

“But you did that in thirty seconds,” the astonished woman replied.

“No,” Picasso said. “It has taken me forty years to do that.”

Grid Shortcomings

This grid doesn’t explain how long a long time horizon actually is. This is done purposefully. There’s no way to calculate how long certain things take to accrue compounding gains. Others, such as money, can be tracked with a bit more finesse (i.e. if you assume 10% gains per year you can model out how much money will be in your account 40 years from now).

This grid doesn’t take fun into account. In my Python example, if I wasn’t having fun learning, then what was the real point of compounding? Why should I dedicate lots of time to something that doesn’t satisfy me? Always be sure that you’re compounding things that matter and bring you joy.

Compounding, when executed correctly, is magic. It can transport your money and abilities from ordinary to spectacular gains. What is that big, lofty goal you’re trying to achieve? How can you break it up into daily opportunities for growth every single day? If you can figure it out, you may have tapped into a superpower hidden within us all.

Life’s only as confusing as you let it be,

Ross

If you enjoyed today’s Gridology post, please consider forwarding it to your friends, family, or colleagues. As always, please reply to this note or find me on Twitter if you have any feedback, have ideas for a post, or want to collaborate.