Thank you all for the meaningful feedback on my post last week. It was great hearing from so many of your. We are all on this journey together. I hope Gridology can continue to be a place you come to help sort out the personal and professional questions that arise in your life.

Now, on to today’s grid:

5-min read

It feels right to follow up last week’s post with a grid regarding how we all learn and grow. Right now, the country feels like it’s going through a massive learning moment. It’s looking like this learning moment is leading to an even larger societal transformation. I stumbled on this tweet that really captures the mood:

Learning shapes opinions. That’s not a groundbreaking thought. What often gets overlooked is that during adolescence we don’t have much control over what we learn and how we learn it. Usually the formula looks like this:

Family: Your opinions are affected by what you learn from your immediate and extended family. Conversations had over the dinner table mold your points of view. Your family decides what movies and television shows you watch. How your family engages with society teaches you how you should act in similar situations.

Friends: Your opinions, especially at an early age, are influenced by the people you spend the most time with. In turn, the opinions of your friends’ parents also tend to creep into how you see the world. Often, your friends are chosen by proximity and randomness, i.e. classmates and neighbors.

Grade School: Your opinions are shaped by what your teachers want you to learn. As a student, you typically don’t have control over what historical events you learn about or, more importantly, how you learn about them. You often don’t get to choose your teachers or classes either.

These three inputs formally control our opinions until we leave the nest. However, by the time we leave our hometowns and families and venture out into the world, we’ve already mistaken our own opinions as our own opinions rather than as the output of the system in which we were raised. Once we leave home, we often seek out new friends similar to the ones we’ve already had. We learn about the subjects that already interest us. We develop a comfort zone.

Adult learning is a way to grow: to unlearn our teachings from the past and relearn on our own terms. Before George Floyd was killed, I had recently finished reading Tara Westover’s acclaimed memoir, Educated. The book is a wonderful coming-of-age story where, over time, Tara realizes that many of her beliefs were built on lies from her naïve upbringing. She held certain opinions because she legitimately didn’t know better. Upon realizing that, she sought her own sources and formally controlled all three of the inputs above: shunning members of her family, acquiring new friends outside of her normal sphere, and choosing her classes, teachers, and books for herself.

Our opinions define us. Some opinions, for better or worse, are held deeply. Some opinions require updates in order to be an accepted member of society. You must hold yourself accountable to unlearn, relearn, and grow as the world around you changes. To do so, it starts with self-reflection.

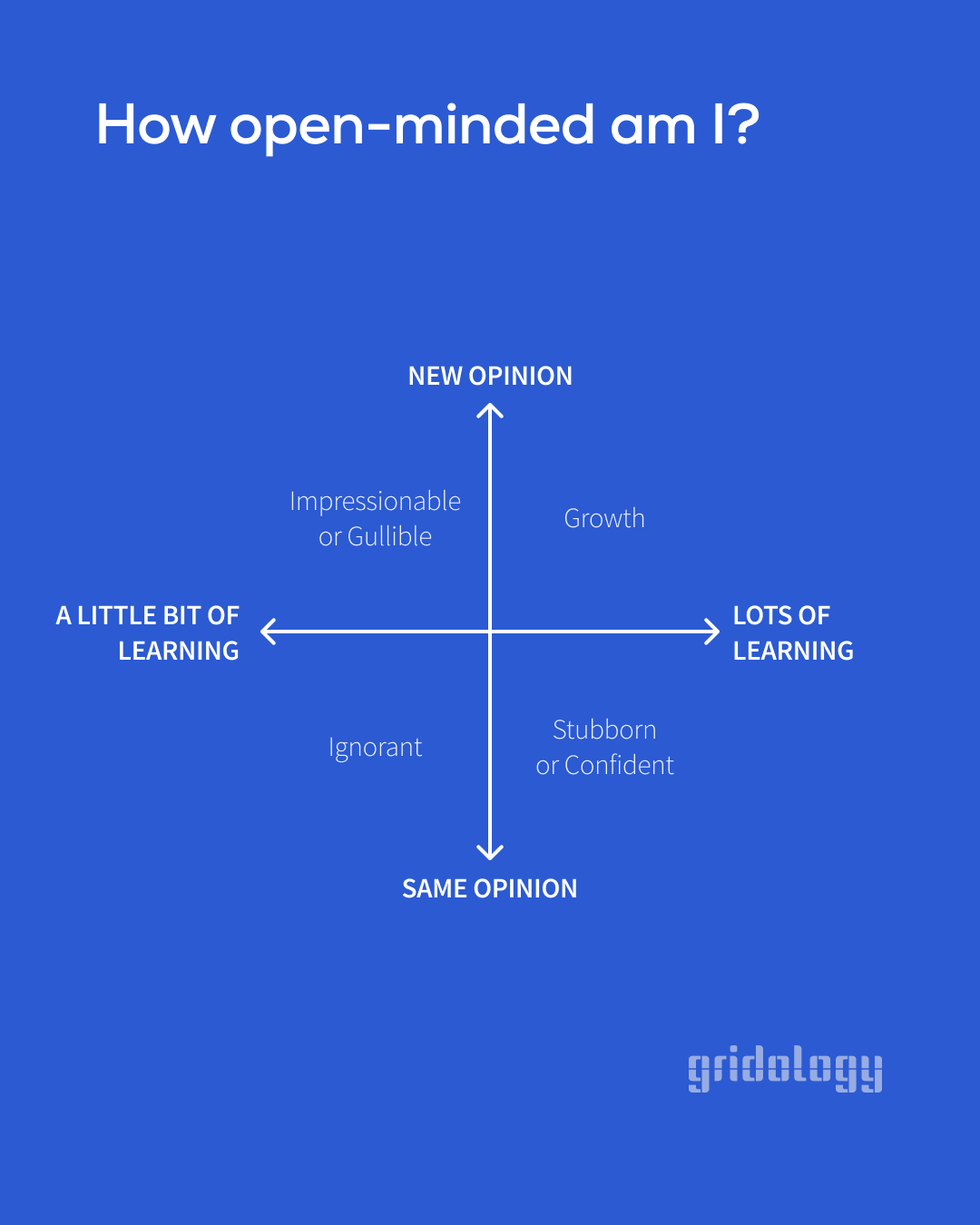

On the x-axis, we have time spent learning something new. How many hours do we put into reading new viewpoints, watching net-new entertainment, or having debates on politics and policy? The key point of this axis is that it must be something new. Time spent learning to further support your current opinion does not count.

On the y-axis, we have your opinion afterwards. This is the cause and effect result of your learning. Does spending time learning something new result in a new opinion? This axis is binary. Your opinion can either stay the same or advance toward the new material.

Understanding the Grid

When using this grid, map specific topics rather than yourself as a whole. For example, map how you learn and grow about racism, privacy regulation, immigration, healthcare, or finance as separate points on this grid. Mapping yourself as a whole doesn’t make sense as opinions you hold differ in their importance.

Using this grid requires quite honesty, humility, and self-awareness. It requires admitting to yourself that the views you hold could be wrong.

The most important question you should be asking yourself is this: Do you fully understand why people hold the opposite opinion as you? If the answer is yes, you’re either rightfully confident in your own decision or too stubborn to change it. If the answer is no, it’s time to do the work and start learning.

Growth

After lots of learning, your opinion changes. In this case, the careful examination of opposing viewpoints helped you identify the shortcomings in your current set of beliefs. This is best embodied by Tara Westover—her ability to identify her gaps and fill them in with knowledge made her grow. As she matured, beliefs that worked for her adolescent-self did not work for her present-self. She took in new facts to replace the old. It takes self-awareness to recognize that your current views are not the views you want for your future. It takes humility to do the work and grow. In the face of new learning, Tara’s opinions were broken down and rebuilt stronger.

Stubborn or Confident

After lots of learning, your opinion stays the same. In this case, you are so set in your beliefs that no amount of reading, listening, or engaging of the other side is able to change the way in which you think about this topic. You are either incredibly stubborn and set in your ways or confident that the opposing viewpoint does not fit in with the type of person you want to be. A good example here are environmentalists: activists who take the time to read the counterarguments claiming climate change is not man-made. These people read the other side of the argument so they can build the right set of talking points to refute it. Despite any study that may come out rejecting climate change, environmentalists will never change their opinion that humans are causing harm to the environment based on the way we live.

Impressionable or Gullible

After just a little bit of learning, your opinion changes. In this case, you’re easily influenced in either a good way or bad way. One possibility is your current beliefs are so misguided that it takes a little bit of information to “enlighten” you. Sometimes listening to a personal story can immediately change your point of view on a topic. Usually your opinion changes quickly because it wasn’t held deeply (potentially because the issue may had been unimportant to you or because you hadn’t done enough research yet to know better). Your adolescent autopilot settings were on, meaning the reason you had the point of view you did was because it fit in with the general theme of the more important views you hold.

The other possibility here is that you’re easily fooled. The rise of misinformation and fake news on social media platforms can be highly impressionable, causing you to rethink loosely held beliefs to better respond to content you are seeing in real time. When new learning tricks you into changing your mind on a topic, it’s clear you didn’t spend enough time deeply learning the facts.

Ignorant

After a little bit of learning, your opinion stays the same or you don’t even attempt to embark on any learning at all. In this case, there’s no desire to learn or grow. You’re often set in your ways, and you don’t spend time learning about the alternatives. There’s no internal drive to change or improve. Sometimes the lack of drive stems from beliefs being held so deeply that learning about the opposing viewpoint serves no purpose. I’d argue that learning about the other side of any issue is always important. At the very least, it can help you persuade those with that differing opinion to change or see your side. When people feel like they don’t have a stake in an issue, they tend to ignore it. Thus, apathy and ignorance go hand in hand. While we all can’t be concerned with every issue, we can certainly do a better job caring about the ones that influence our society, health, and culture.

Grid Shortcomings

There are two shortcomings with this grid:

This grid ignores the type and quality of content you are learning from. Reading books, in my opinion, is more valuable than watching cable news. Having difficult conversations with real people in person is more valuable than reading hot takes on your social media feed. Learning comes in all formats. Time spent is just a proxy way to measure the time, quality, and impact of the content.

This grid ignores changes in your opinion where your opinion actually doesn’t advance towards the learning but just becomes stronger. There is no way for this grid to capture how learning about new things can have an adverse effect: where you forcefully reject what you are learning and read counterpoints as further evidence that supports your own point of view. Instead of changing your opinion, your belief becomes more deeply held.

Using this grid can help you answer the question: What do I need to see, read, or believe to change my opinion on a topic? Being honest with yourself is the critical first step.

Recognize what opinions you hold only because you’ve done the self-assigned and required 360-degree learning. We all deserve to be the best, well-rounded version of ourselves. To do so, it means digging into topics that are foreign and uncomfortable in hunt for a greater truth.

Life’s only as confusing as you let it be,

Ross

If you enjoyed today’s Gridology post, please consider forwarding it to your friends, family or colleagues. If you have any feedback or have other ideas you’d like me to tackle, just reply back to this note!